Why Is the Flu Seasonal?

Though it’s still warm and beautiful out, winter looms on the horizon. Winter in Florida can be good: a time for family, biking and outdoor exercise, bigger waves for surfing, and tasty foods. Winter can also be bad: a time for cold, wetsuits, fruitcakes, and the flu. So what is the flu, how does it work, and why does it take after my extended family and only visit us in the cooler months?

The seasonal flu is caused by the flu virus, properly called Influenza, and more properly a type of orthomyxoviridae (there will be a test at the end). There are three categories of influenza viruses that infect humans, conveniently named influenza A, B, and C. These are distinct from each other in some critical ways, one being how easily they change the proteins on the outside of the virus. Viruses are tiny little packets of DNA or RNA that are contained in a little pouch. The pouch has special proteins called antigens on the outside that help it invade target cells. The proteins are also one of the key ways our immune system detects and fights these viruses. Influenza A changes these rapidly, influenza B changes slowly, and influenza C is stable, undergoing little or no change over time.

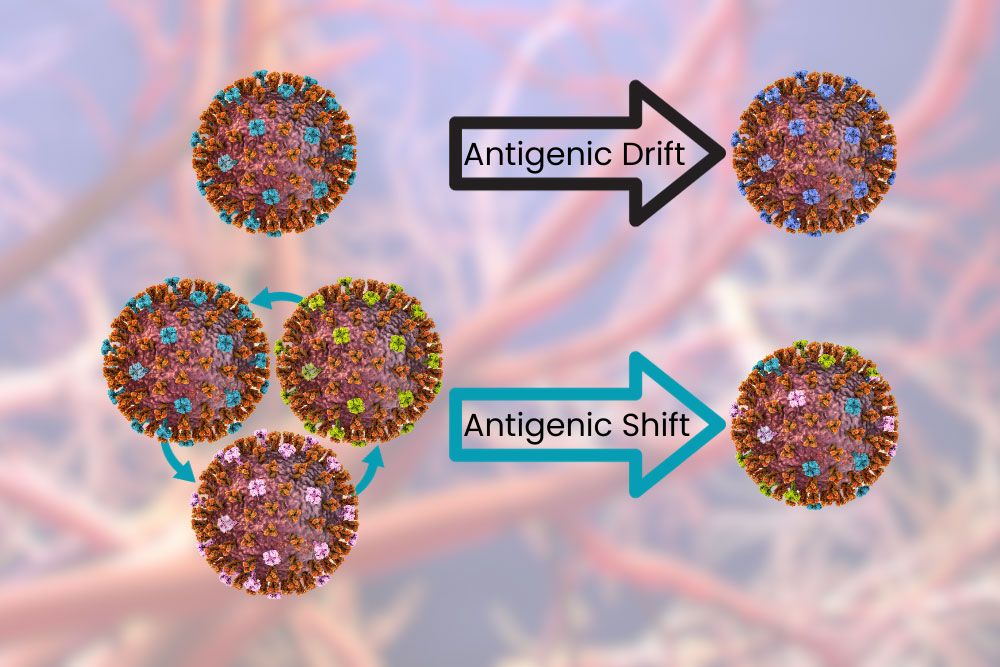

Influenza A and B viruses undergo a process called antigenic drift. This is when the surface proteins change a little bit at a time. The changes can cause incremental “improvements” to the virus, allowing it to evade our immune system and infect cells more easily. These changes are fast enough that over the course of a year your body may not be able to recognize the virus and you may get the flu year after year, but slow enough that you probably won’t get it twice in the same season – especially with a vaccine. Influenza A can also undergo antigenic shift, which is like the antigenic drift on overdrive. This is like when your dad shaves his beard for the first time in 20 years: same thing underneath but different enough you have trouble recognizing him. When this happens your body can’t recognize the virus as dangerous and previous antibodies and vaccines provide little or no aid. Because of this Influenza A has been responsible for all flu pandemics.

Why is it seasonal though? Well, it’s not seasonal everywhere. In some tropical and subtropical areas, the flu follows the rainy season and comes twice a year. In some tropical areas the flu is present year-round. This provides a clue; it’s the weather! Strangely, it might actually be our response to changing weather that is the progenitor of a flu season. Influenza viruses spread through the air. This is bad news for us in that they spread easily from person to person, but also means they are affected by the weather more than things that may be spread by fluids or insects. Temperature and relative humidity are the two biggest factors. Cool, dry air gives influenza viruses a better chance for infecting us. The virus is more stable in droplets, more of them are shed, and the droplets might stay in the air longer as they evaporate. Our defensive capabilities are decreased in the cold – anyone with a dry throat can attest to this. The protective mucus layer in our airway is decreased and the innate immune system isn’t as efficient. To make things worse, in the winter we spend more time indoors.

In the industrialized world, including America, we spend almost no time outdoors. A 2001 study found that we spend around 87% of our time in buildings and 6% in cars. This varies heavily by where you work, but most of us spend almost our whole lives in buildings with recirculated, conditioned air. In the winter, heated air is drier, which promotes influenza virus stability. As we walk into and out of buildings our throats are dry and inefficient at removing viral particles. This creates ideal conditions for Influenza to infect and spread during the winter.

So what can we do? Get vaccinated of course! Every year scientists work hard to produce vaccines that will target the most likely versions of influenza to emerge during the winter. Antigenic drift is taken into account and vaccines will (hopefully) protect against the likely minor antigenic changes between production of the vaccine and emergence of flu season. New mRNA vaccines shorten the time between production and deployment of vaccines based on the current dominant strain, increasing their effectiveness. All flu vaccines available in the USA are quadrivalent, meaning they protect against two strains of influenza A and two strains of influenza B. So don’t forget to get a flu vaccine, spend time with the family, and go outside!

Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD). (12 December, 2022). How flu viruses can change: “drift” and “shift”. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/change.htm

Couch, R. B. (1996). Orthomyxoviruses. Medical Microbiology. 4th edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8611/

Klepeis, N. E., Nelson, W. C., Ott, W. R., Robinson, J. P., Tsang, A. M., Switzer, P., … & Engelmann, W. H. (2001). The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. Journal of Exposure Science & Environmental Epidemiology, 11(3), 231-252. https://www.nature.com/articles/7500165

Lowen, A. C., & Steel, J. (2014). Roles of humidity and temperature in shaping influenza seasonality. Journal of virology, 88(14), 7692 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4097773

Moriyama, M., Hugentobler, W. J., & Iwasaki, A. (2020). Seasonality of respiratory viral infections. Annual review of virology, 7, 83-101. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-virology-012420-022445