New Research on Heart Failure: Understanding IL-6 and Inflammation

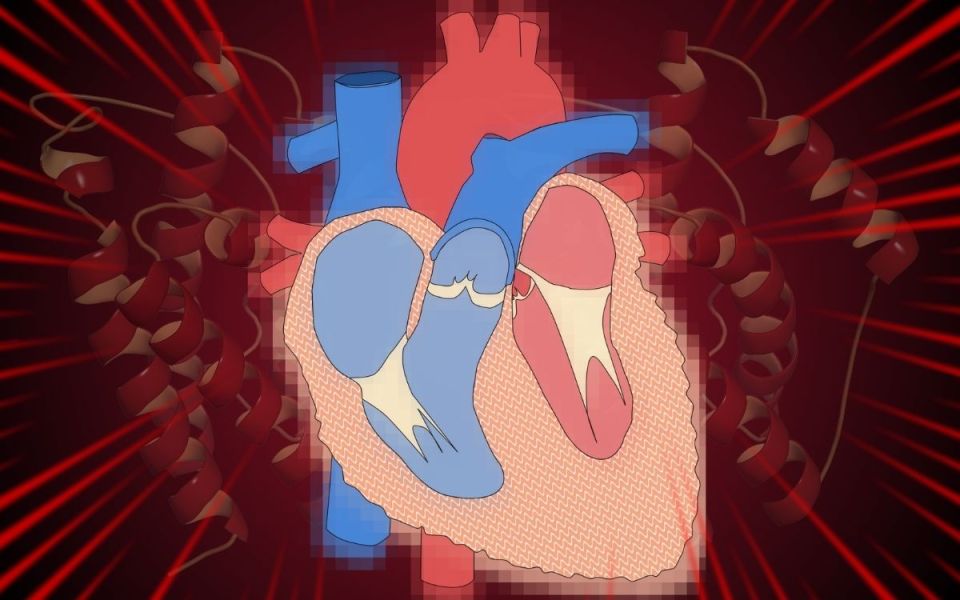

Heart failure is a widespread condition affecting over 6.6 million Americans [1]. In heart failure, the heart pumps insufficient oxygenated blood to meet the body’s oxygen needs. The two main categories of heart failure are Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction (HFrEF), and Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction (HFpEF).

- Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction means the heart is too weak to empty the heart chamber

- Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction means the walls of the heart are thicker and become stiffer, reducing the total volume of blood available to be pumped

The number of people with heart failure is rising, and the proportion of people with HFpEF is increasing [2]. Heart failure symptoms include fatigue, weight gain, swelling in the lower parts of the body, and shortness of breath, especially when exercising or lying down [3]. Risk factors for heart failure include coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and low socioeconomic status [4]. Underlying these risks is an even bigger, overarching problem: chronic inflammation [5, 6, 7, 8].

Inflammation is the body’s response to damage. This is obviously necessary when we have an infection or trauma, but when inflammation becomes chronic, or long-term, parts of the body (including the heart) can’t handle it. If the heart was a lifeguard, inflammation would be a kid screaming “I’m drowning!” When one kid is drowning, this signal is perfect. In the body, an inflammation signal called Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is one of the key alert signals when things go wrong [6, 9, 10]. When the heart experiences damage, IL-6 helps the body limit cell death, helps increase wound repair, and tells immune cells to activate [9]. Chronic inflammation is as though everyone just yells “I’m drowning” all the time for fun, the lifeguard either burns out trying to save everyone or stops caring and responding to the call. With chronic inflammation, heart muscle and heart walls are damaged, muscles become thickened, and some cells deposit “helpful” collagen that turns into fibrosis [4, 6, 9, 11]. In the end, the heart responds much like our lifeguard, either by reducing the ejection fraction or by thickening the walls of the heart until its capacity is reduced.

Chronic inflammation has a more sinister side as well. IL-6 is both a cause and an effect of heart failure [8]. When researchers measure IL-6 in people, they find that increased levels independently predict who will get heart failure and who will suffer most from it [6, 7, 12]. But IL-6 isn’t limited to just the heart. Age, other heart conditions, and iron deficiency can increase IL-6 levels even without a serious event like a heart attack or stroke [12]. In addition, high IL-6 throughout the body can increase diseases that make heart failure worse, including frailty, kidney disease, atrial fibrillation, and iron levels [8]. It’s like all the other kids at the pool yelling when they see the lifeguard jump in; it just serves to make everything more confused and dangerous.

The obvious solution to this problem is to try to regulate IL-6 levels and stop chronic inflammation. The idea isn’t to stop saving drowning people, but to calm everyone down so that those who are actually in trouble can be saved without burning out the lifeguard. Monoclonal antibody medications are currently in development which target IL-6 to help reduce chronically high levels. If these trials prove successful, we may have a real life preserver on our hands.

Creative Director Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

|

Click Below for ENCORE Research Group's Enrolling Studies |

|

|

|

Click Below for Flourish Research's Enrolling Studies |

References:

[1] Martin, S. S., Aday, A. W., Almarzooq, Z. I., Anderson, C. A., Arora, P., Avery, C. L., ... & American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. (2024). 2024 heart disease and stroke statistics: a report of US and global data from the American Heart Association. Circulation, 149(8), e347-e913. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001209

[2] Oktay, A. A., Rich, J. D., & Shah, S. J. (2013). The emerging epidemic of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Current heart failure reports, 10, 401-410. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3870014/

[3] Centers for Disease Control. (15 May, 2024). About Heart Failure. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/about/heart-failure.html

[4] Groenewegen, A., Rutten, F. H., Mosterd, A., & Hoes, A. W. (2020). Epidemiology of heart failure. European journal of heart failure, 22(8), 1342-1356. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ejhf.1858

[5] Redfield, M. M. (2016). Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(19), 1868-1877. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp1511175

[6] Chia, Y. C., Kieneker, L. M., van Hassel, G., Binnenmars, S. H., Nolte, I. M., van Zanden, J. J., ... & Eisenga, M. F. (2021). Interleukin 6 and development of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the general population. Journal of the American Heart Association, 10(11), e018549. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/JAHA.120.018549

[7] Deswal, A., Petersen, N. J., Feldman, A. M., Young, J. B., White, B. G., & Mann, D. L. (2001). Cytokines and cytokine receptors in advanced heart failure: an analysis of the cytokine database from the Vesnarinone trial (VEST). Circulation, 103(16), 2055-2059. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/01.CIR.103.16.2055

[8] Murphy, S. P., Kakkar, R., McCarthy, C. P., & Januzzi Jr, J. L. (2020). Inflammation in heart failure: JACC state-of-the-art review. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 75(11), 1324-1340. https://www.jacc.org/doi/full/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.01.014

[9] Fontes, J. A., Rose, N. R., & Čiháková, D. (2015). The varying faces of IL-6: From cardiac protection to cardiac failure. Cytokine, 74(1), 62-68. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4677779/

[10] Abernethy, A., Raza, S., Sun, J. L., Anstrom, K. J., Tracy, R., Steiner, J., ... & LeWinter, M. M. (2018). Pro‐inflammatory biomarkers in stable versus acutely decompensated heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Journal of the American Heart Association, 7(8), e007385. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/JAHA.117.007385

[11] Paulus, W. J. (2020). Unfolding discoveries in heart failure. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(7), 679-682. https://www.nejm.org/doi/abs/10.1056/NEJMcibr1913825

[12] Markousis‐Mavrogenis, G., Tromp, J., Ouwerkerk, W., Devalaraja, M., Anker, S. D., Cleland, J. G., ... & van der Meer, P. (2019). The clinical significance of interleukin‐6 in heart failure: results from the BIOSTAT‐CHF study. European journal of heart failure, 21(8), 965-973. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ejhf.1482

Additional Reading

Tsao, C. W., Lyass, A., Enserro, D., Larson, M. G., Ho, J. E., Kizer, J. R., ... & Vasan, R. S. (2018). Temporal trends in the incidence of and mortality associated with heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction. JACC: heart failure, 6(8), 678-685. https://www.jacc.org/doi/full/10.1016/j.jchf.2018.03.006