New Liver Meds Take New Approaches

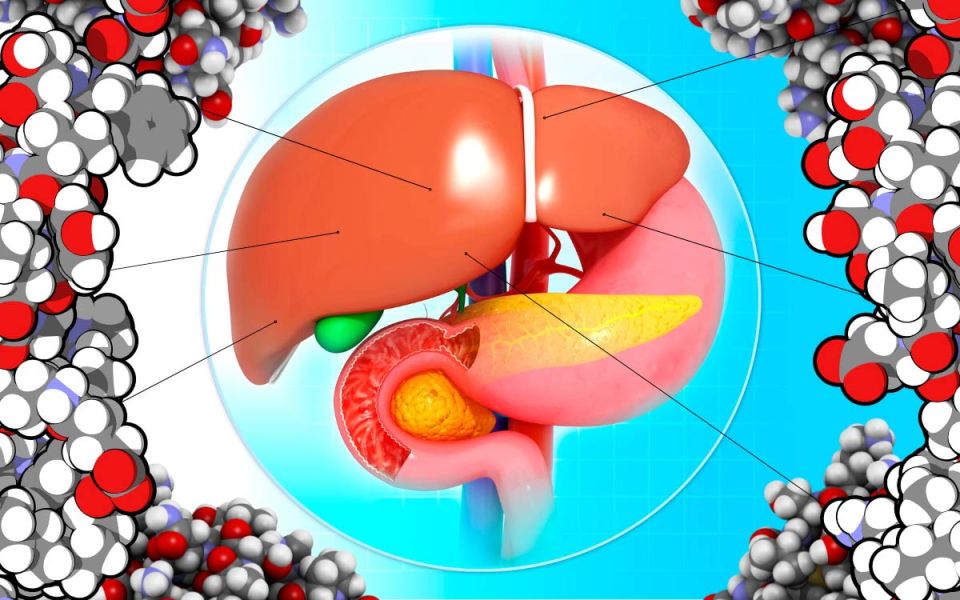

The liver is an amazing and complex organ. It can regenerate from damage, helps us digest and function, filters some toxins, and in return gets thoroughly abused by us humans. Alcohol can damage the liver, but most livers are mistreated through other means, like diabetes and obesity. This is visible in the form of accumulated fat in the liver and can lead to serious problems. Nearly 1 in 4 adults in America have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). When a fatty liver becomes inflamed and damaged it is called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH. NASH is dangerous and is an indication of decreased liver health. If untreated, NASH will degrade the liver, potentially leading to scarring known as fibrosis and permanent cirrhosis. Cirrhosis is cirrhiously bad.

At this time, there are no approved therapies for the treatment of NASH. The current standard of care is exercise and weight loss to alleviate problems that damage the liver. Unfortunately, much like trying to lick your elbow, this is easier said than done. The consequences of an impaired liver include liver failure, cirrhosis, cancer, cardiovascular disease, and more. To alleviate this burden, scientists have identified several medical approaches to combating fatty liver. These approaches generally target the underlying mechanisms that lead to a fatty liver, aiming for a long-term solution. The broadest categories for investigative NASH medication are managing fat, sugar, and inflammation in the liver.

One of the liver’s major jobs is to balance the body’s energy storage needs by managing fat. One method of dealing with excess fats is to dump extra fats out of the body through the digestive system. Thyroid hormone receptor beta (THR-β) can help us do just that. Receptors are parts of a cell that detect what’s happening outside its borders. They interact with hormones, sugars, fats, or other things. Each receptor only reacts to specific molecules. When activated, THR-β may help reduce the accumulation of fats in the liver by telling the body to move fats from the liver to the gut. Medications that activate THR-β are being investigated to see if they can also do this.

Another method of helping the liver manage fat is to stop fats from being created in the first place. Unfortunately, some people create an unhealthy amount of fat. They may have a mutated gene called PNPLA3. PNPLA3 genetic disorder affects how the fat cells in the body deal with triglycerides. This mutation can increase liver fat and possibly lead to NASH. Scientists are working on ways of suppressing this gene.

Other research targets being studied for limiting fat production include peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARα). This is a chemical receptor on liver cells that regulates how fats are processed. When activated, this receptor can lower fat creation and lead to lower blood triglycerides (the most common type of fat). Rampant activation can be dangerous, however, so very specialized Selective PPARα Modulator (SPPARMα) medications are being developed to target the system with specificity and finesse. These medications also target and activate a very interesting hormone called fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), which we will cover in the next section.

Fats can’t take all the spotlight, though, because one of the biggest culprits of liver damage is actually sugar. As a cookie lover, this makes me very sad. Sugars, also called glucose, are converted into fats (stored in the liver) and can damage the liver, metabolic system, heart, etc. The body detects high levels of sugar in the pancreas. High blood sugar signals the release of insulin and amylin from the pancreas to the liver. The liver then starts breaking down, converting, and storing sugars. A couple of medications look to target this system to lower the burden on the liver and help with NASH. Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), mentioned above, has broad effects, including in the pancreas. It helps manage the body’s metabolism and homeostasis and makes the pancreas more sensitive to insulin. This may be particularly helpful for people with insulin resistance. Insulin resistance leads to type 2 diabetes. FGF21’s other effects appear to include increasing energy use, potentially leading to weight loss. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists, like Semaglutide, Trulicity, and Mounjaro, act on the same system. These directly attach to pancreatic cells, preparing them for a large insulin release when they detect high glucose levels. It is hoped that this can help the liver deal with high blood sugar without taking damage. Another potential pathway to managing blood sugar is to send it down the yellow-brick road. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors deal with blood sugar by expelling it out of the body with urine.

The final target of potential NASH treatments is inflammation. NASH stands for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, which literally means “non-alcoholic inflammation of the liver (due to) fat.” Inflammation is like a visit with the inlaws: good when it doesn’t last too long. Researchers hope that reducing chronic inflammation may help limit the damage of NASH and prevent a worsening of the disease. Luckily, two avenues of treatment above also target inflammation. One complication of the PNPLA3 genetic mutation is an increase in cyclophilin, a protein that can increase inflammation. By reducing excess cyclophilin through PNPLA3 management – or by targeting it directly, inflammation may be relieved. Interestingly, FGF21, which may be used to lower blood sugar, appears to lower inflammation in the pancreas. The hope is that these medical interventions may also help the liver downstream.

Overall, the liver is complex, and trying to keep it from being damaged is difficult. The only real treatment available today is weight loss through diet and exercise. With luck and help from the clinical trial process, there may be new avenues available in the future.

References:

Fisher, F. M., & Maratos-Flier, E. (2016). Understanding the physiology of FGF21. Annual review of physiology, 78, 223-241. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev-physiol-021115-105339

Geng, L., Lam, K. S., & Xu, A. (2020). The therapeutic potential of FGF21 in metabolic diseases: from bench to clinic. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 16(11), 654-667. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41574-020-0386-0

Prasad, A. S. V. (2019). Biochemistry and molecular biology of mechanisms of action of fibrates–an overview. International Journal of Biochemistry Research & Review, 26(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.9734/ijbcrr/2019/v26i230094

Shen, J. H., Li, Y. L., Li, D., Wang, N. N., Jing, L., & Huang, Y. H. (2015). The rs738409 (I148M) variant of the PNPLA3 gene and cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Journal of lipid research, 56(1), 167-175. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4274064/

Sinha, R. A., Bruinstroop, E., Singh, B. K., & Yen, P. M. (2019). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hypercholesterolemia: roles of thyroid hormones, metabolites, and agonists. Thyroid, 29(9), 1173-1191. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6850905/

Ure, D. R., Trepanier, D. J., Mayo, P. R., & Foster, R. T. (2020). Cyclophilin inhibition as a potential treatment for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 29(2), 163-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13543784.2020.1703948

US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institute of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (April, 2021). Definition & facts of NAFLD & NASH. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/nafld-nash/definition-facts

Wang, P., & Heitman, J. (2005). The cyclophilins. Genome biology, 6(7), 1-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1175980/