Navigating the Ups and Downs of POTS: Understanding Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome

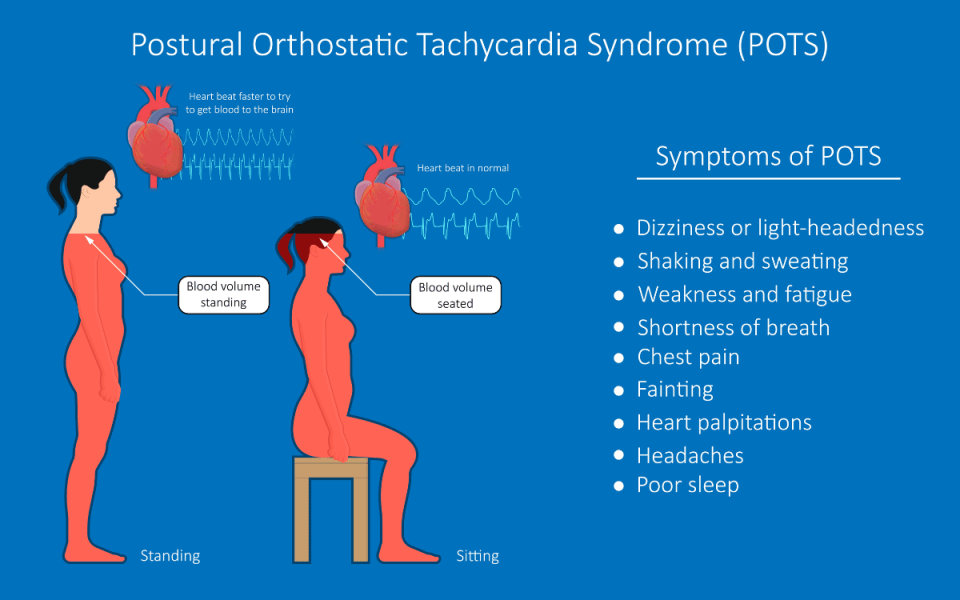

Most of us have experienced standing up and feeling a little light-headed. This is caused by gravity pulling blood into the legs, causing the brain to run a teensy bit dry. Within a few seconds, the vessels in the legs tighten and push blood out, and the heart pumps it up to the brain so we can forget where we left our glasses. For some people, it’s not quite as simple – or as harmless. Between 500 thousand and 3 million Americans, mostly women between 15 and 50 years of age, suffer from Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome, or POTS. Postural means it relates to your position. Orthostatic comes from the Greek for “upright” and “to stand.” Tachy- means fast, and -cardia refers to the heart; together, tachycardia means the heart is beating excessively fast. Syndrome actually means a group of symptoms happening together, which is an important part of POTS. Together, Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) is an abnormal increase in high heart rate when standing up from a lying position.

POTS has two aspects that occur together: tachycardia when standing and orthostatic intolerance. Tachycardia is a very high heart rate. With POTS, this is defined as 30 beats per minute (BPM) more than normal (40 in children) or a BPM of 120 or more. Orthostatic intolerance means the patient can’t stay upright without experiencing symptoms. Symptoms include:

- Lightheadedness and fainting

- Blood pressure changes

- Shaking

- Trouble concentrating

- Nausea

- Trouble exercising

- Coldness in legs

- Chest pain

- SOB (shortness of breath)

- Cold, red/blue discoloration of legs

As alluded to earlier, POTS occurs because of gravity. When we stand up, around 2 cups (500mL) of blood falls into our lower body, and we must push and pull it back out. Baroreceptors in the cardiovascular system detect the change in blood pressure and kick the autonomic nervous system (which does things automatically) into action. The brain rapidly sends signals to redistribute blood (especially to get more blood up to the brain!) Blood vessels push out blood. They constrict, squeezing blood out and providing less space to pool up. The heart pulls blood up. If not enough blood is coming up, it beats faster to try to help. With POTS, the autonomic system breaks down somewhere, and the heart starts beating out of control to try to help.

POTS is a syndrome, not a disease. This is significant because syndromes like POTS can have many causes and can be hard to precisely parse into perfunctory pieces. Any part of the system described above can be out of whack and potentially cause POTS. The brain might not receive proper signals or might not send signals in a helpful way. Our ability to squeeze blood vessels might be compromised. We might have hormone imbalances, sensitivities, or changes. The amount of blood or salt in the body might be too low. Some people find their blood pressure decreases slightly with POTS, but some find that their blood pressure increases! Conditions that can cause these differences vary widely. Small vessel muscles can weaken, pregnancy, surgery, and trauma may cause POTS, and autoimmune or infectious diseases can affect things. Genetics, diabetes, and poisoning from alcohol, heavy metals, or chemotherapy may also be implicated. The common factor is that the heart tries very hard to pump blood to the brain and doesn’t think it’s succeeding. In cases where it does fail, the brain goes into standby mode, and we faint.

With all of these possible mechanisms, no solution to POTS can hope to work for everyone. Treating underlying causes is a good start, if applicable. Beyond that, each case is unique, and sufferers must talk with a medical professional to find a solution that works for them. There are no approved medications for POTS, but a doctor may prescribe something off-label that could work in a specific case. Non-medicinal remedies include drinking more water (soda does NOT count), eating more salt, and compression leggings. These should go to the waist to avoid blood pooling about the knees. The best long-term solution is physical conditioning – exercise. This can be very difficult in severe cases of POTS as it can cause exercise intolerance. A good goal is around 20-30 minutes of aerobic exercise three times a week. As with all lifestyle and medication changes, talking to a medical professional is a good idea. With POTS and its varied causes, signs, and symptoms, it is critical.

Staff Writer / Editor Benton Lowey-Ball, BS, BFA

References:

Dysautonomia International, (2019). Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome. https://dysautonomiainternational.org/page.php?ID=30

Grubb, B. P. (2008). Postural tachycardia syndrome. Circulation, 117(21), 2814-2817. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/circulationaha.107.761643

Olshansky, B., Cannom, D., Fedorowski, A., Stewart, J., Gibbons, C., Sutton, R., … & Benditt, D. G. (2020). Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): a critical assessment. Progress in cardiovascular diseases, 63(3), 263-270. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9012474/

Raj, S. R. (2006). The postural tachycardia syndrome (POTS): pathophysiology, diagnosis & management. Indian pacing and electrophysiology journal, 6(2), 84. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1501099/